Featured Article

Kent State Earns Institutional Excellence Award for Diversity Efforts

Kent State University has been awarded the 2014 Institutional Excellence Award by the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education.

read moreA Double Twist Reveals a Liquid Crystal’s Deep Blue Color

Posted March 31, 2014 | Cindy WeissKent State researchers find new dimensions in the nanostructure

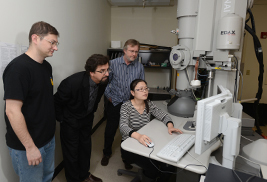

Researchers who collaborated on the Nature

Communications paper are, left to right, Nick Diorio, Ph.D.,

postdoctoral researcher; Oleg Lavrentovich, Ph.D.,

Trustees Research Professor; Antal Jákli, Ph.D., professor;

and seated at the TEM microscope, graduate student Cuiyu

“Tracy” Zhang.

Twenty years ago, Antal Jákli’s research specialty – bent-core liquid crystals – took him to Germany, where he and his labmates joked that the material they were studying looked like opals – it was so solid and colorful, it could have been used in jewelry.

Now he knows why. In a paper published Feb. 19, 2014, in Nature Communications, Jákli, Ph.D., professor of chemical physics in the Liquid Crystal Institute at Kent State University, and his research colleagues showed that the same material that he studied in Germany has structural color.

Structural color does not fade over time like colors produced by pigments or dyes. It is present in some living organisms – in peacock tail feathers and butterfly wings, for example. It can be found at the nano-level, at a scale more than 50,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair. And that is where Jákli’s group found evidence of structural color in a B4 phase bent liquid crystal, using cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at Kent State’s Liquid Crystal Institute.

The TEM microscope was installed at the Liquid Crystal Institute two years ago with funding from a $15 million Ohio Third Frontier grant. It allows researchers to examine and photograph thin slices of liquid crystals, seeing a three-dimensional view of structural patterns. The TEM is “the key to understanding nanostructures of lots of liquid crystals that we were not able to understand before,” Jákli says.

The article in Nature Communications describes experiments carried out by Jákli’s Ph.D. student, Cuiyu “Tracy” Zhang, on the TEM. Nick Diorio, a Liquid Crystal Institute postdoctoral researcher, added X-ray measurements to the work. The results were then analyzed and interpreted by Jákli and Oleg Lavrentovich, Ph.D., Trustees Research Professor at Kent State.

They found that the liquid crystal had nano-filaments twisted together and stacked on top of each other in a “double twisted” structure; double because the filaments were themselves twisted into a helix, giving the blue color.

While the high-tech TEM was instrumental in the discovery, the researchers used a decidedly low-tech resource to visualize the structure: pasta. Jakli bought twisted dry pasta at Acme ($2 a box), and they layered 300 noodles in a pan, lasagna-style, then vertically vibrated it for half an hour to see the resulting alignment.

Because the liquid crystal spontaneously forms a helix, it does not have the chirality, or left-handedness versus right-handedness, typically found in molecules. This is the first known structurally colored liquid crystal material with no molecular “handedness.” That would provide flexibility in manufacturing applications and could make the material 10 times cheaper to use than materials with chirality, Jakli says.

Potential uses would be in solar cells, paint, anti-counterfeiting devices and credit card security strips.

Finding the double-twist structure and showing its role in the liquid crystal’s color offers new avenues for basic research, too. It expands a “rich world” of learning more about structural color throughout nature, Jákli says.

In addition to the TEM facility funding, the research project was supported by National Science Foundation grants.